Dispelling Myths About Occupation Laws and Examining Owner and Tenant Protections

Introduction

Nicaragua’s property landscape is shaped by a complex history of land reforms, political upheavals, and evolving legal frameworks. Questions often arise about whether the country has an “occupation law” that allows individuals to move into a home and claim legal residency, leaving owners powerless. This notion, reminiscent of exaggerated squatter’s rights in other jurisdictions, does not accurately reflect Nicaraguan law. Instead, property rights are grounded in the nation’s Constitution and Civil Code, which emphasize private ownership while providing safeguards for tenants and mechanisms to address unauthorized occupation. This article explores the facts based on legal texts, government reports, and expert analyses, detailing the rights of property owners and tenants. It also incorporates visual elements to illustrate key concepts, including photographs of typical Nicaraguan housing and judicial settings, as well as graphical representations of property dispute data.

Nicaragua’s property system draws from civil law traditions, with roots in Spanish colonial codes updated through modern reforms. The 1987 Constitution (with amendments) guarantees private property under Article 44, stating that it serves a social function but is protected from arbitrary interference. However, historical events like the Sandinista revolution’s land expropriations in the 1980s have left a legacy of disputes, affecting up to 35-40% of properties as per World Bank estimates from 2017. Foreign investors, including U.S. citizens, are advised by entities like the U.S. Embassy to exercise caution due to risks of title conflicts and enforcement challenges.

Traditional Nicaraguan homes, often featuring colorful colonial architecture in cities like Managua or Granada, symbolize the cultural importance of property ownership. Yet, beneath this picturesque facade lie legal intricacies that can lead to protracted disputes.

Legal Framework for Property Ownership

Nicaragua’s property laws are primarily governed by the Civil Code (dating back to 1904, with reforms), the Constitution, and specific statutes like Law No. 509 (1981) on agrarian reform and Law No. 277 (1997) on land registration. Property is divided into real (immovable, such as land and buildings) and personal (movable). Ownership can be acquired through purchase, inheritance, gift, or, in rare cases, adverse possession (known locally as usucapión or prescripción acquisitiva).

Foreigners enjoy equal rights to own property as nationals, per the Foreign Investment Law (Law 344), but restrictions apply near borders (within 5-15 km) and coasts for security reasons. Coastal areas fall under Law 702 (2007), designating the first 200 meters from high tide as public domain, with the initial 50 meters inalienable. Registration in the Public Registry of Property is mandatory to secure titles, involving deeds notarized and filed with cadastral surveys.

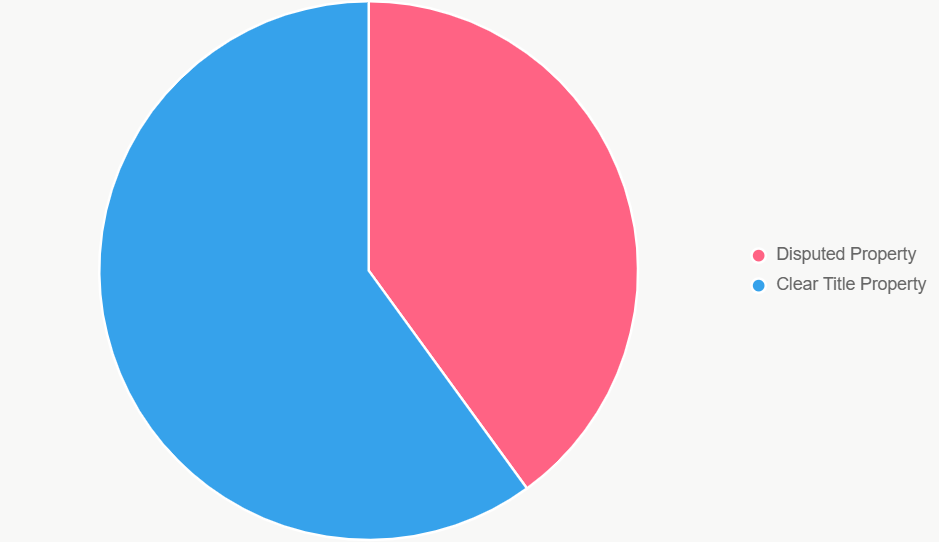

Despite these protections, the system is plagued by historical issues. During the Sandinista era, around 28,000 properties were expropriated, leading to ongoing claims. As of the 1990s, over 5,000 claims involving 16,000 properties were filed, with only about 60% resolved, according to government figures from 1995. This backlog contributes to uncertainty, where multiple parties may claim the same land.

This pie chart illustrates the scale of disputes, highlighting that a significant portion of Nicaraguan land remains contested, often due to incomplete titles or past reforms.

Rights of Property Owners

Owners in Nicaragua hold fundamental rights to use, enjoy, and dispose of their property, as enshrined in the Constitution’s Article 44. These include the ability to sell, lease, or mortgage assets, with protections against arbitrary seizure. The state can only expropriate for public utility, with fair compensation. In practice, however, enforcement can be weak due to judicial inefficiencies and corruption.

For instance, in cases of unauthorized occupation, owners can initiate eviction through civil courts or police intervention if the intruder is recent. Law emphasizes that private property is inviolable, but owners must act promptly. If a squatter improves the property (e.g., builds structures), they may claim compensation under “indemnización por mejoras,” but this does not grant ownership outright. Owners are also responsible for taxes: annual property tax at 1% of cadastral value, and transfer taxes at 4%.

Challenges arise in rural or indigenous areas, where communal titles (propiedad comunal) require community consent for sales. In such regions, like the Atlantic Coast, individual claims can be invalidated if they ignore collective rights. Additionally, “afectación familiar” designations protect family homes, requiring spousal consent for transactions.

Recent government actions, including confiscations of over 452 properties from opponents since 2018, underscore political risks to ownership. These are often justified under anti-terrorism or sovereignty laws, but international bodies like the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) have criticized them as violations of property rights.

Visit Managua on a trip to Nicaragua | Vernon Charvis

Court buildings in Nicaragua, such as the National Palace in Managua, serve as venues for resolving property disputes, though processes can drag on for years due to backlogs.

Rights of Tenants

Tenants, or arrendatarios, are protected under the Civil Code’s lease provisions (Articles 1440-1500). Leases can be fixed-term or periodic, and tenants have the right to peaceful enjoyment without interference. Key protections include:

- Notice Requirements: Landlords must provide advance notice for termination—typically 30 days for month-to-month leases.

- Prohibition on Self-Help Eviction: Owners cannot forcibly remove tenants; they must obtain a court order.

- Rent Control and Increases: While not strictly controlled, increases must be reasonable and agreed upon.

- Maintenance: Tenants can withhold rent if the property is uninhabitable, but must notify the landlord.

In urban areas, Law No. 278 (Urban and Rural Lease Law) provides additional safeguards, requiring written contracts and protecting against unjust eviction. Tenants who have resided for extended periods (e.g., 10 years) may pursue usucapión, but this requires court notification to the owner and proof of good faith possession.

However, tenants face vulnerabilities in informal arrangements, common in rural Nicaragua. During the COVID-19 era, temporary moratoriums on evictions were enacted, but these have lapsed. International reports note that while laws exist, enforcement favors landlords in corrupt systems.

Squatters, Adverse Possession, and the “Occupation Law” Myth

The idea of an “occupation law” allowing immediate legal residency upon moving in is a myth. Nicaragua does not have statutes permitting instant squatting without recourse for owners. Instead, adverse possession (usucapión) allows title acquisition after prolonged, uninterrupted possession in good faith.

Details vary, but sources indicate:

- For ordinary usucapión: 10 years with just title (e.g., a flawed deed).

- For extraordinary: 30 years without title, requiring open, peaceful possession. (From global comparative law, as Nicaragua follows civil code norms similar to those of other Latin American countries.)

One blog notes that after 1 year of uninterrupted good-faith occupation without eviction requests, rights may accrue, but this likely refers to preliminary protections, not full ownership. Squatters can be evicted via police if recent (within days/weeks) or through civil courts otherwise. However, in practice, authorities may hesitate, especially in politically sensitive areas.

Protests over land grabs highlight tensions, as seen in demonstrations against government expropriations.

A Road to Dialogue After Nicaragua’s Crushed Uprising …

Such events underscore the real-world impacts of property conflicts on communities.

Eviction Processes

Eviction (desalojo) requires due process under the Civil Procedure Code. Steps include:

- Written notice to the tenant/squatter, specifying breaches (e.g., non-payment, lease end).

- If ignored, file a lawsuit in local courts.

- A court hearing, where evidence is presented.

- If ruled in favor, a judge issues an eviction order, which is enforceable by the police.

For squatters, expedited processes exist if possession is recent. However, delays are common—cases can take months or years—and outcomes may be influenced by bribery. A 2025 circular reportedly requires courts to consult police before evictions, further complicating matters.

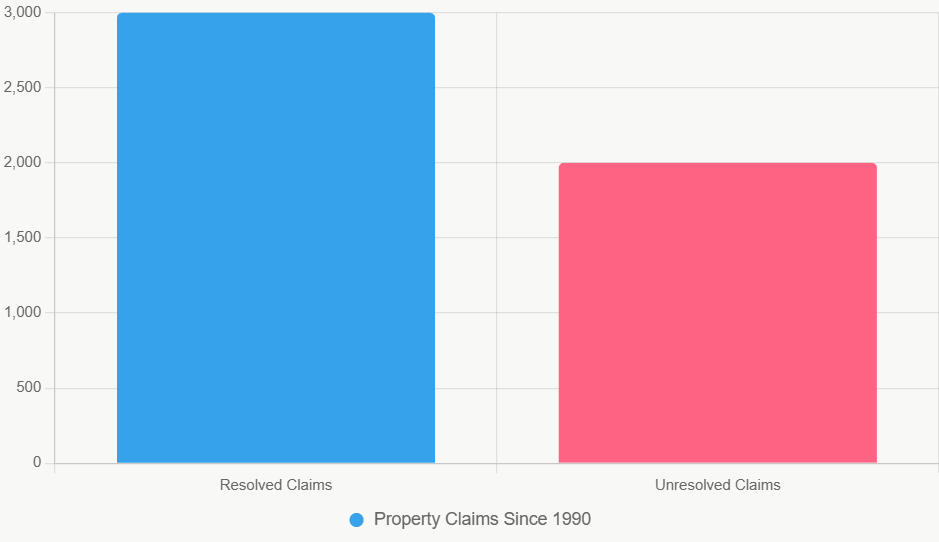

This bar graph shows the resolution status of historical claims, reflecting systemic inefficiencies.

Property Disputes and Statistics

Disputes often stem from unclear titles, Sandinista-era confiscations, or indigenous claims. The World Bank notes 35-40% of properties in some form of conflict. Since 2018, new invasions have surged, with government seizures valuing millions. Rural areas see higher rates due to agrarian reforms benefiting 112,000 individuals.

The Carter Center’s reports highlight that while laws aim for equity, corruption undermines them. Expatriates report cases where squatters resist eviction, but legal recourse exists if pursued diligently.

Colonial-style houses in Granada exemplify properties at risk of disputes due to historical layers of ownership.

Conclusion

Nicaragua does not have an “occupation law” granting immediate rights to intruders; instead, owners can evict through legal channels, though challenges like delays and corruption persist. Tenants enjoy protections against arbitrary removal, balancing the scales in a system rooted in social equity. For potential investors, thorough due diligence— including title searches and local legal advice—is essential. As the country navigates political and economic shifts, reforms could strengthen enforcement, reducing disputes and bolstering confidence in property rights.